Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Four

by Brad Westwood

Native Americans lived in what is now Salt Lake’s west side. After Europeans began to colonize North, South, and Central America, the Great Basin became a site where many different people and nationalities claimed ownership. In this post, we will consider how the Native Americans of the Salt Lake Valley interacted with both the land and Western European colonization.

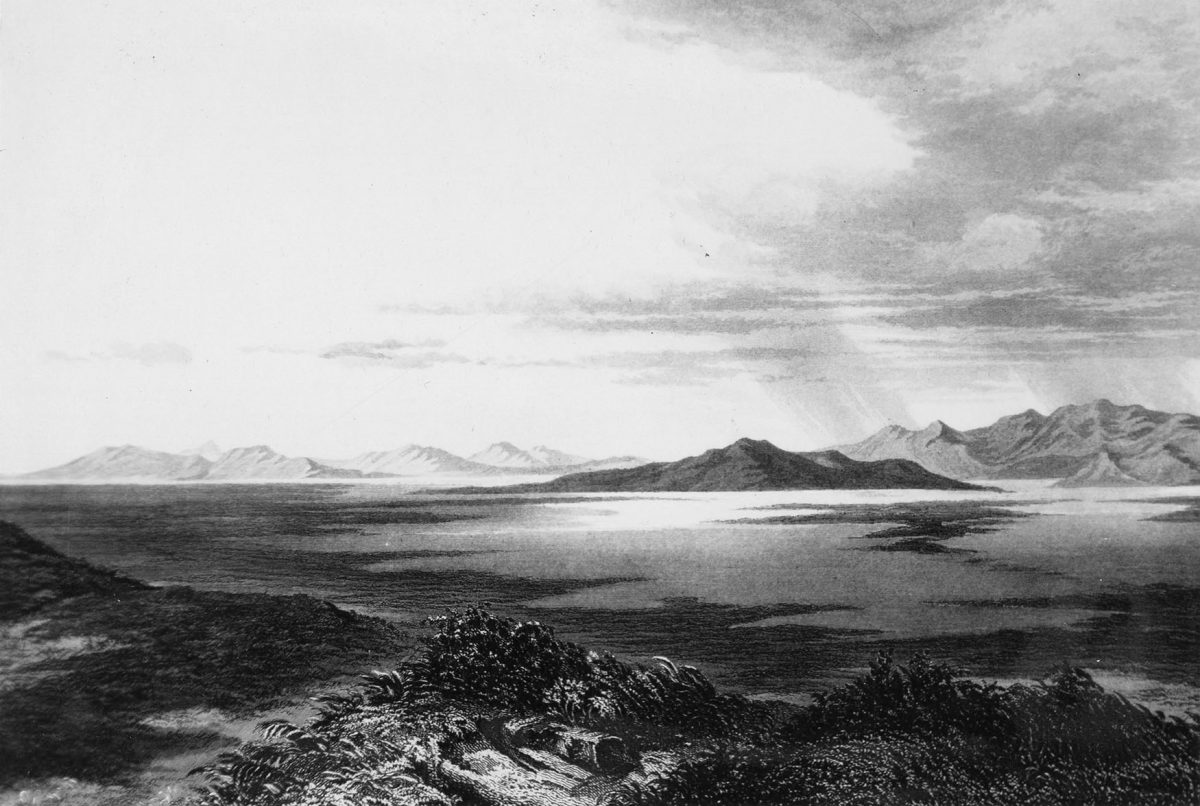

Ancient peoples used what is now the Pioneer Park neighborhood for over a millennium for hunting, camping, and agriculture. Archeologists have discovered evidence of human life around the Great Salt Lake that dates back 13,000 years. In fact, researchers have discovered numerous artifacts related to the Fremont culture dated from A.D. 700 to 1400 in nearby areas and across the Salt Lake Valley. In more recent centuries, riparian zones adjacent to rivers, creeks, springs and surrounding grasslands, up and down the Salt Lake Valley, served as seasonal camps and hunting grounds for Ute, Shoshone and Goshute tribes. Native American groups across the region also harvested salt from the Great Salt Lake. A network of active trails crisscrossed the valley and every adjacent canyon, evidence that abundant nomadic life, trade, hunting, and communication permeated the area. Archeological history from the Salt Lake Valley also tells us that ancient Utahns acquired and traded goods across the Great Basin and as far away as the Pacific Coast and the Midwest.

Likely western European hunters explored all of Utah’s mountainous rivers and streams. Beginning in the late seventeenth- to the early-nineteenth centuries, Spanish, Mexican, French, British, and Anglo-American trappers and traders traversed the Rocky Mountains and Great Basin. These Euro-American traders worked with Native American groups to locate hunting spots to meet an insatiable international market for small animal pelts. Especially popular were beaver pelts that furriers used to make hats and other clothing pieces. One of the most well-known fur trappers of this era was Jedediah Smith (1799-1831), who, after traveling across most of the American West, declared Salt Lake Valley as a crossroads and his home away from home. Taken from Smith’s journal, dated June 22, 1827, historian Dale Morgan first highlighted Smith’s words about this valley:

“Those who may chance to read this at a distance from the scene may perhaps be surprised that the sight of this lake surrounded by a wilderness of more than 2000 miles diameter excited in me those feelings known to the traveler who, after long and perilous journeying, comes again in view of his home. But so it was with me for I had traveled so much in the vicinity of the Salt Lake that it had become my home of the wilderness.”

Jedediah Smith

Utah and the Salt Lake Valley were the uncharted northern lands of New Spain until 1821 when Mexico gained its independence from the Spanish Empire. After the Mexican-American War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) resulted in the transfer of what is now the American Southwest to the United States. As a result of this treaty, Utah territory became part of the nation’s public domain. The settlement also stipulated that the United States was then considered responsible for resolving any Native American land rights and claims.

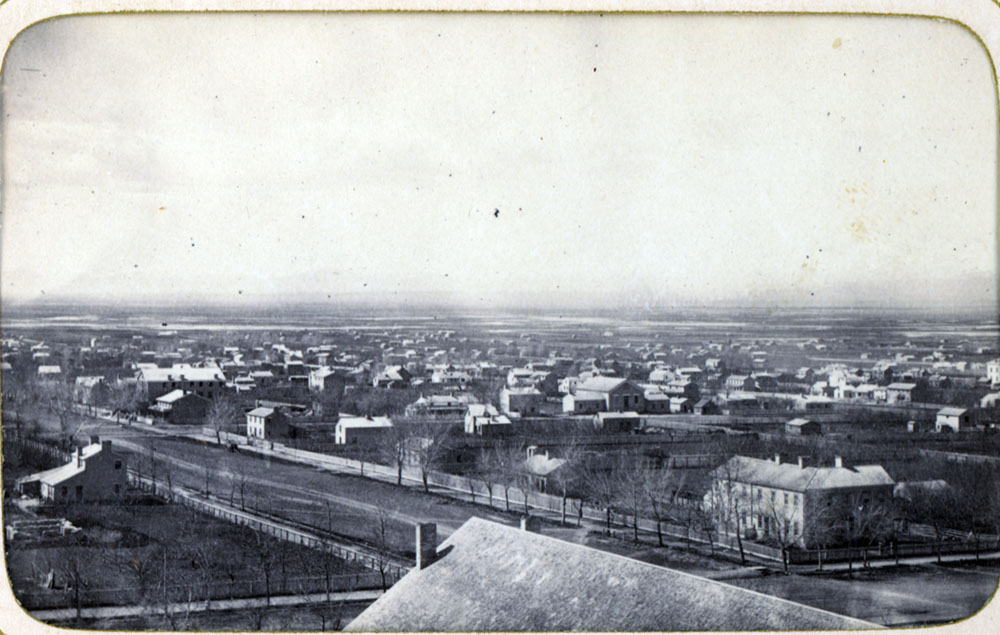

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo did not include any formal wording recognizing Native American ownership of Utah or the southwestern lands. As such, white settlers chose to deny or ignore Native American sovereignty or land claims. Additionally, the Federal Government also refused to recognize Native American sovereignty in 1862 with the Passage of the Homestead Act that offered western lands to prospective eastern settlers. Regardless of the claims of the Federal Government, Utah’s tribal peoples continued to claim what is now Salt Lake City and the surrounding mountains and valleys as their homelands. In writing this series Salt Lake West Side Stories, we make clear that all that comes hereafter occurred on Native American ancestral lands. We also note that Spanish and Mexican citizens and Hispano-American explorers participated in the process of trade and culture-sharing that created the first European contact with Utah’s lands and original peoples.

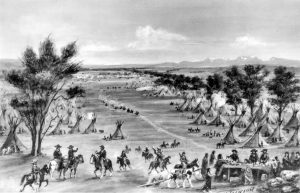

For the first ten to fifteen years after Mormon immigrants entered the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ (also referred to as “Mormons”) President and Prophet Brigham Young preached and directed members to live peaceably with Native Americans and to respect their nomadic and hunter-gather activities. However, the colonizers simultaneously encroached and restricted the Native Americans’ use of ancestral camping, hunting lands, and waterways. Mormon settlers also influenced and regulated Native American trade and trade networks, which undermined the livelihood and economic base of each of the region’s diverse American Indian groups. As a result of Mormon encroachment, hostilities erupted between Native peoples and pioneer colonizers.

In 1852, Brigham Young called for Mormon colonists to feed Utah’s nomadic peoples. His call, along with other instances of Native American and settler conflicts over land, trade, and ideologies resulted in exacerbated tensions, increased hostility, and the development of systems of support and subjugation. The tribes’ justifiable efforts and failures at warring with their invaders during the 1850s and 1860s (which included the Walker, Tintic, and Black Hawk wars) eventually drove Utah’s Native American peoples to settle on lands outside of their original settlements. In the long view, the Mormon colonist’s treatment of Utah’s Native American people was the same as how Americans treated Native American groups throughout the United States.

In the late 1860s into the 1880s, the Federal Government adopted and funded a policy that drove the United States’ Native American peoples onto reservations. Along with Utah’s various reservations (all far beyond the Wasatch Front), a majority of Utah’s Native Americans now live across the Wasatch Front. The contemporary Native American communities in Salt Lake City are supported by their tribal affiliations by many organizations, including the Urban Indian Center of Salt Lake (120 West 1300 South), also on the west side, a mile south of Pioneer Park.

“The Salt Lake Valley was not a tabula rasa—or blank slate. Nor were the Native Americans simply part of the natural history of the valley. Salt Lake was, and is, a place in constant use, as a crossroads and as a home, for many peoples for at least thirteen millennia.“

Considering the ancient archeological record, the more recent Native American history, and the early European and American explorer records, a recurring theme becomes evident: The Salt Lake Valley was not a tabula rasa—or blank slate. Nor were the Native Americans simply part of the natural history of the valley. Salt Lake was, and is, a place in constant use, as a crossroads and as a home, for many peoples for at least thirteen millennia.

We hope you join us for the next installment of Salt Lake West Side Stories. In the following three posts, we will discuss the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and their relationship to Salt Lake’s west side, including the building of a pioneer fort.

Do you want to read the next post (Post 5)? FROM PIONEER VANGUARD TO PIONEER FORT

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Related Activities: Visit the Natural History Museum of Utah (301 Wakara Way above the University of Utah) and experience the Native Voices exhibition. The exhibit was designed in cooperation with Utah’s Native American communities and includes artifacts that represent Great Basin American Indian arts and culture that physically display a “deep memory” and contemporary presence of Utah’s indigenous people.

Visit and experience the 250-acre Galena Soo’nkahni Preserve that is on 12300 South and 800 West in Draper, on the Jordan River Parkway Trail. The Galena Soo’nkahni Preserve includes a large sundial containing eight separate monuments (dedicated in 2015) representing Utah’s tribes. The preserve is located near a 3,000-year-old village which archaeologists have indicated may be the earliest known location of corn farming in the Great Basin.

Contributors: Special thanks to the following people who contributed to this post. Dr. Phillip Natoriani (adjunct professor, Ethnic Studies Department, University of Utah, and former director, Utah Division of State History and the Utah State Historical Society), Shirlee Silversmith (former director, Utah Office of Indian Affairs) and Dr. Richard Talbot (archeologist and director, Office of Public Archeology, Brigham Young University).

This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Readings: Thomas G. Alexander, Brigham Young and the Expansion of the Mormon Faith (University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2019) 71-105, 271-304, 330-331.

Becoming Utah: Native Americans and the Long Road to Political Representation, Thrive125 (Utah’s 125th statehood anniversary) film series.

Todd Cromar, “Archaeologists discover proof of wetlands, ancient life on the Utah Test and Training Range,” 75th Hill Air Force Base Public Affairs, July 22, 2016.

Scott J. Eldridge, Fred R. Gowans, “The Fur Trade in Utah” Utah History Encyclopedia.

Dale L. Morgan, Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., Indianapolis and New York, 1953) 214.

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – [email protected]